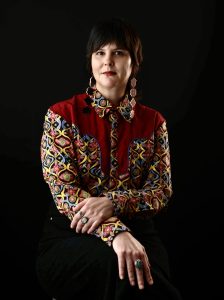

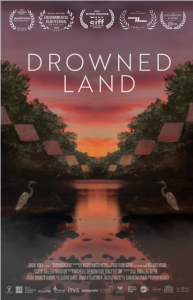

Colleen Thurston (BA ‘08) is an award-winning documentary filmmaker, educator, and curator whose work centers Indigenous perspectives and our relationship to the natural world. A citizen of the Choctaw Nation and a seventh-generation Oklahoman, Colleen has created work for the Smithsonian, public television, tribal nations, and major film festivals. She is a two-time Emmy Award winner for her work on the series Osiyo, Voices of the Cherokee People, and has been recognized as a Firelight Media Documentary Lab Fellow and a Sundance Institute Indigenous Film Fund Fellow. In addition to filmmaking, she currently works as a programmer for the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival, is the project producer for Native Lens, and holds a Tulsa Artist Fellowship. Next month, her feature documentary Drowned Land – a deeply personal story about water, land, and memory – will screen at the Loft Film Fest.

Colleen Thurston (BA ‘08) is an award-winning documentary filmmaker, educator, and curator whose work centers Indigenous perspectives and our relationship to the natural world. A citizen of the Choctaw Nation and a seventh-generation Oklahoman, Colleen has created work for the Smithsonian, public television, tribal nations, and major film festivals. She is a two-time Emmy Award winner for her work on the series Osiyo, Voices of the Cherokee People, and has been recognized as a Firelight Media Documentary Lab Fellow and a Sundance Institute Indigenous Film Fund Fellow. In addition to filmmaking, she currently works as a programmer for the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival, is the project producer for Native Lens, and holds a Tulsa Artist Fellowship. Next month, her feature documentary Drowned Land – a deeply personal story about water, land, and memory – will screen at the Loft Film Fest.

We caught up with Colleen to talk about her filmmaking journey, the power of place-based storytelling, and the lasting influence of her time at the University of Arizona School of Theatre, Film & Television (TFTV).

Your feature film Drowned Land interweaves the story of Oklahoma’s Kiamichi River, community activism, and your own family history, including your grandfather’s work on dam construction. How did you approach telling a story that connects both ancestral legacy and environmental justice?

When I was developing the film, I would pitch the story in labs, in fellowships, and to trusted friends and mentors, and I was often asked what my connection to the story was. I’d share that my grandfather helped build some of the dams around Eastern Oklahoma that displaced some of the very people this film was about: rural Oklahomans, many of them Indigenous like my family. Each time I shared that, people would say, “That’s the angle that makes this story unique.” And eventually I came to accept that too: including my personal story and this exploration of ancestral legacy – both from the perspective of being from a displaced tribe myself and also benefitting from my grandfather’s work with the Army Corps of Engineers – is a uniquely complex and nuanced entry point to a documentary that deals with the commodification of natural resources, and the history of displacement of Indigenous people due to that commodification.

You’ve explored the idea of giving legal rights to natural entities like rivers – a concept rooted in both Indigenous worldviews and contemporary environmental movements. How did you come to engage with this idea, and how has it shaped your work as a filmmaker and advocate?

I approached the filmmaking process as a collaboration with the documentary’s protagonists and the community at the heart of it. Sandy and Charlotte, two protagonists of Drowned Land, brought forward the idea behind the Rights of Nature and granting legal personhood for non-human entities. That became a core message that we wanted to amplify through the film. This movement has gained a foothold throughout the world, and several rivers have been legally recognized as retaining personhood with certain inherent rights. This idea – this worldview – has fundamentally impacted how I came to position the Kiamichi River in our film. Like our human protagonists, she is introduced with a title card and acknowledged in the credits. I developed a relationship with her as I would a friend, and learned to talk with her and interact with her – considering her as a collaborator. As an advocate for the protection of all life sources, I think it’s important for all of us to recognize how intertwined we are with our water ways. Humans are mostly water, and rivers give us life – sustaining us with drinking water, and providing life to plants and animals as well. We exist here on earth because of them, and they should be revered in the highest regard.

I approached the filmmaking process as a collaboration with the documentary’s protagonists and the community at the heart of it. Sandy and Charlotte, two protagonists of Drowned Land, brought forward the idea behind the Rights of Nature and granting legal personhood for non-human entities. That became a core message that we wanted to amplify through the film. This movement has gained a foothold throughout the world, and several rivers have been legally recognized as retaining personhood with certain inherent rights. This idea – this worldview – has fundamentally impacted how I came to position the Kiamichi River in our film. Like our human protagonists, she is introduced with a title card and acknowledged in the credits. I developed a relationship with her as I would a friend, and learned to talk with her and interact with her – considering her as a collaborator. As an advocate for the protection of all life sources, I think it’s important for all of us to recognize how intertwined we are with our water ways. Humans are mostly water, and rivers give us life – sustaining us with drinking water, and providing life to plants and animals as well. We exist here on earth because of them, and they should be revered in the highest regard.

So one thing we ask audiences to consider is Where Does Your Water Come From? When you turn on the tap, where does that drinking water travel from to sustain you? What’s the name of that river or water source, who are the people who steward the water now and who did traditionally, and what are the needs of that water – does it need protection, or a voice or platform to amplify its needs?

You were brought on as a programmer at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival by former Executive Director – and current TFTV faculty member – Jen Gerber, and you’ve now been with the festival for five years. How did that opportunity shape your work as a curator, and what have you taken away from your time programming for one of the country’s leading documentary festivals?

I love this question! I’ve been working in film festivals since 2010, and before that I volunteered and interned at a few festivals including the Tucson Film Festival when I was in undergrad around 2006-2007. I met Jen several years ago through the incredible documentary film network in Arkansas and came to know Hot Springs Doc Fest as this wonderfully supportive festival. Hot Springs is the largest film festival I’ve worked for – we screen around 40 features and 60 shorts over 10 days. Notably, it’s an Oscar qualifying festival, so joining this team was an opportunity to help showcase some of the strongest docs that are pushing the form forward each year. I absolutely love getting to platform the work of filmmakers who care deeply about the craft, and who are dedicated to sharing stories from diverse perspectives, experiences and cultures around the globe.

When Jen hired me at Hot Springs, I suggested that since the festival typically falls over Indigenous Peoples Day in October, we create a spotlight for Indigenous-made films. Hot Springs has since dedicated a programming track to Indigenous films; this year we screened five shorts and five features. In the past few years, we’ve also centered Indigenous films in our educational programming, during which middle and high school students from around the state join us for special screenings and extended Q&As with members of a film’s team, offering an opportunity for hundreds of students to learn about cultures and experiences that aren’t always included in classroom curricula.

Over the past three years we’ve included Paige Bethmann’s Remaining Native, a coming-of-age story of a young Paiute runner dedicated to raising awareness and healing around Native American Boarding Schools, Ivy and Ivan MacDonald’s When they Remain, about buffalo rematriation on the Blackfeet Nation, and Jesse Shortbull and Laura Tomaselli’s Lakota Nation vs. the United States, a strikingly gorgeous testament to the long history of broken treaties and the fight to protect Lakota land.

A few years ago, we also featured a retrospective of Ho-Chunk/Pechanga filmmaker Sky Hopinka’s work and honored him with the Brent Renaud Career Achievement award. I’m very proud to lead the Indigenous programming at Hot Springs, and to be able to champion the amazing films we showcase across the festival program every year.

You’ve supported many Native storytellers through your work as an educator, filmmaker, and festival curator. What advice would you offer students in film school, especially Indigenous students, who are learning the craft, finding their storytelling style, and looking to build a path in film?

I would say to learn everything and take from it what suits you, your community and your practice. Learn the basics of editing and cinematography even if you know you want to be a producer, because it will help you communicate with your team. Same goes for any other role.

Watch EVERYTHING! Build a strong foundation of film history so you understand references, homages, and how this art form has grown. Diversify your genres – you might watch a horror film that incorporates a visual strategy that you in turn want to utilize in a documentary.

I would also suggest focusing on how you want to change and build this industry and this art form. While this can be an ego-driven industry, it’s dependent on community, and individual success is determined by the success of our teams. Treat other people well, treat everyone with respect and give credit where credit is due. I also always suggest approaching each project with an ethical strategy – considering how do you want to work with your crew? How do you want to work with your actors or protagonists? What kind of care do you need to provide? How do you reject extractive filmmaking or harmful practices? Are you the best person to be telling this story, or are you potentially silencing someone else’s voice or taking away an opportunity from someone within the community you’re telling the story about? Really think about your approach to HOW you work, rather than simply the end product. And always practice gratitude. Your film and your work will reflect the care you put into it and how you treat your collaborators.

And finally, a question we love to ask our alumni: who at TFTV inspired you and how did your experience at the school shape your path as a filmmaker?

When I was at U of A, I had the opportunity to focus on production as much as studying theory and aesthetics of filmmaking, which provided me with a strong understanding of the field, the history of the craft, and of media literacy.

I took some incredible courses that have impacted me to this day: Experimental Filmmaking with Nicole Koschmann, and History of Documentary with Beverly Seckinger. In fact, it was an assignment in Professor Seckinger’s class that influenced my career the most. She assigned a “documentary subgenres” project, in which I chose to research environmental documentaries. I remember watching Blue Vinyl, Koyaanisqatsi, The Gleaners and I and An Inconvenient Truth in that class, as well as a documentary about the artist Andy Goldsworthy. I was captivated by these stories that intertwined land stewardship, explorations of earth-first narratives, and interrogations of the environmental effects of capitalism. I fell in love with Agnes Varda and deepened my appreciation for avant-garde narrative techniques. After graduation, I pursued an MFA in Montana State University’s Science and Natural History Filmmaking program and have been working in environmental and culturally based media narratives in film and television ever since.

I’m incredibly grateful for the well-rounded film and television education I received at the U of A and am excited to be back this fall screening my film in Tucson!

'Drowned Land' at the Loft Film Fest